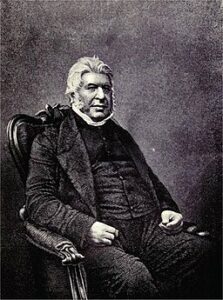

Hook arrived in Leeds as its new Vicar in 1837, aged 39, to a hostile reception, finding a town already beset with massive social problems as its population exploded, and a church that, failing to adapt, was overwhelmed, dysfunctional, ineffective and excluded the poor.

Hook arrived in Leeds as its new Vicar in 1837, aged 39, to a hostile reception, finding a town already beset with massive social problems as its population exploded, and a church that, failing to adapt, was overwhelmed, dysfunctional, ineffective and excluded the poor.

Hook was a man of deep Christian faith and convictions, who believed faith was measured not by words alone or intensity of religious feelings, but by action, and above all by action on behalf of the poor. His actions sought not only to alleviate directly the distress of extreme poverty, but to improve the social and working conditions of working class men, women and children and to transform their life chances through the provision of education.

He left 22 years later, burnt out, but hugely popular, with an astonishing record of achievement on behalf of the local population and the Church of England in Leeds, and widely held to be the ‘the greatest parish priest in the country’.

Forty years later the popular memory of him was still strong enough to ensure that when four statues were erected in City Square to honour major Civic figures in Leeds’ past, one of them depicted him.

So who was Walter Hook, what did he achieve and (why) does he matter today?

When Walter Hook arrived in Leeds in 1837, the town was experiencing rapid change as the Industrial Revolution transformed it from a small textile town into a major industrial centre with the world’s first woollen mill and a canal system extending to the port of Liverpool. Its population almost tripled from 53,000 in 1801 to 150,000 in 1841.

When Walter Hook arrived in Leeds in 1837, the town was experiencing rapid change as the Industrial Revolution transformed it from a small textile town into a major industrial centre with the world’s first woollen mill and a canal system extending to the port of Liverpool. Its population almost tripled from 53,000 in 1801 to 150,000 in 1841.

But this growth came at a considerable human cost. The poorest lived in overcrowded, dirty houses with little sanitation, much of it in areas close to the Parish Church. Diseases like cholera and typhus claimed hundreds of lives. Children were forced to work in mills and factories, often in dangerous conditions. Many children received no education at all, as at that time there was no state education, and most schools were run by charities, usually the Churches.

The Church of England in Leeds, hampered by its structures and legal restrictions, was in the doldrums and unable to respond to the challenges posed by the changes in the world around it.

Hook met all these challenges head on with energy, courage and determination. He became a vocal campaigner for the rights of workers to dignity, education and improved working conditions, and he set about renewing the Church in Leeds by increasing capacity and changing the organisational structures so that more local clergy would be available in the areas where the population was growing.

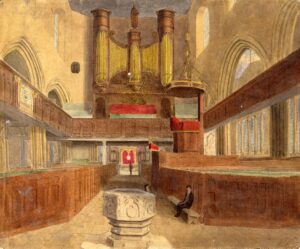

Leeds Parish Church had been rebuilt multiple times over the centuries. The building Hook found when he arrived dated from the 14th century, and was struggling to keep up with the needs of Leeds and its surging population, especially once his abilities as a preacher became known.

The building did not meet Hook’s vision for worship. At a time when most people only received Holy Communion once or twice a year, Hook believed everyone should receive it much more frequently. But the large screen in the middle of the church hid the altar, where Holy Communion takes place, from view and halved the church’s capacity.

Within months it was agreed that the church should be rebuilt, and a subscription scheme started to fund it, with Hook making the first – and a substantial – donation.

Hook’s instructions to the architect stipulated that the altar should be visible throughout the church, and that there should be space in front of the altar for all to gather to receive communion. This and the positioning of the choir near the altar were revolutionary at the time but set a trend followed almost universally in new churches around the country.

Hook’s instructions to the architect stipulated that the altar should be visible throughout the church, and that there should be space in front of the altar for all to gather to receive communion. This and the positioning of the choir near the altar were revolutionary at the time but set a trend followed almost universally in new churches around the country.

Hook wanted a church that would be awe-inspiring, with choral music on a par with established cathedrals. When it was reopened in 1841, it was the largest new Church in England since St Paul’s Cathedral.

Hook followed this with the creation of 18 new churches during his tenure, and a restructuring of the Parish which ensured that each church had a resident clergyman and increased numbers of free seats for the poor.

Leeds Parish Church was situated close to some of the poorest areas of Leeds, notably the York Road and what was then known as ‘The Bank’ (now called Richmond Hill). He devoted a significant number of his many working hours to help relieve poverty. In addition to being available every day at 10.00am to receive the poor, he spent many hours visiting the poor in these areas, and despite the risks, took the clerical lead at the two cholera hospitals in his care when there was a cholera outbreak.

Hook was keenly aware from his work among the poor how little dignity many working people enjoyed in their lives, with overcrowding, poverty and long working hours creating the sort of pressures that made bringing up children excessively challenging. In the 1840s he became a passionate and vocal supporter of the Ten Hours Movement, a campaign to reduce the hours of women and children in factories, making powerful speeches to huge audiences, in a bid to gain popular and political support for the cause. His courage in doing so was remarkable in that it put him at odds with the wealthy factory owners, whose generosity he was at the time depending on to clear the debts from the rebuilding of the Parish Church! He was recognised as a key figure in the movement in Leeds, and his involvement must have played a large part in the popularity he acquired. The Ten Hours Act came into force in 1847.

On arriving in Leeds, Hook was appalled at the levels of ignorance in a largely uneducated population. At a time when the state provided no education at all, the children of most working class families had no education and were forced to work in the factories from a very young age. As well as swiftly ramping up the number of Sunday School places into the thousands, Hook established the Anglican Board of Education for Leeds, which resulted in the provision of 27 schools. Examples were Christ Church School, Meadow Lane, The Bank National School on Richmond Hill (pictured), and St Peter’s Parish Church School.

On arriving in Leeds, Hook was appalled at the levels of ignorance in a largely uneducated population. At a time when the state provided no education at all, the children of most working class families had no education and were forced to work in the factories from a very young age. As well as swiftly ramping up the number of Sunday School places into the thousands, Hook established the Anglican Board of Education for Leeds, which resulted in the provision of 27 schools. Examples were Christ Church School, Meadow Lane, The Bank National School on Richmond Hill (pictured), and St Peter’s Parish Church School.

However, he was well aware that charities such as the Church could not meet the need in such populous areas. ‘We have lighted a lantern which only makes us more sensible of the surrounding darkness’, he lamented, proposing the radical and at that time contentious solution that the state should provide education in everything except religion, which should be provided by the Churches on a denominational basis. Hook’s proposals were attacked from most sides at the time but beginning in 1870 and progressing over subsequent decades, state education became firmly established in the UK.

Hook’s work on behalf of his fellow citizens made him both highly respected and popular. An example of the respect can be found in the request from striking colliers to be one of three people to nominate an arbitrator as they sought to settle their claim. Similarly, when Queen Victoria came in 1858 to open the new Town Hall, The Friendly Societies asked him to sign an address on their behalf and present it to the Queen. His popularity endured in the shared memory of the city, as is testified by the erection of the City Square statue in 1903.

Hook’s work on behalf of his fellow citizens made him both highly respected and popular. An example of the respect can be found in the request from striking colliers to be one of three people to nominate an arbitrator as they sought to settle their claim. Similarly, when Queen Victoria came in 1858 to open the new Town Hall, The Friendly Societies asked him to sign an address on their behalf and present it to the Queen. His popularity endured in the shared memory of the city, as is testified by the erection of the City Square statue in 1903.

Today, circumstances have in many ways changed, but the church that he built remains and his vision of the purpose and life of the Christian Church continue to challenge and inspire us as we seek to serve the City of Leeds.

We continue to offer uplifting worship enhanced by the building, by choral music and good preaching. We endeavour to offer a place of welcome and sanctuary for those marginalised by society. We work with the Leeds Church Institute, a place of Christian learning founded by Hook, to promote discussion, learning and exploration of what it means to be Christian in the modern world.